Bharuchi Vahora Patel – In Britain

After the end of Second World War of 1939, economic growth started accelerating in Britain. In the early 1950s, various manufacturing sectors, including textile, woollen and allied industries started installing modern machinery. This created new opportunities for the indigenous population who were working in morning and afternoon shifts in the textile and woollen sector to move to the day time jobs created by the economic boom in various fields like aerospace, electronics, motor manufacturing etc. The indigenous population preferred the day time jobs because it did not involve working unsocial hours, which would give them plenty of time to enjoy a social life with their families and friends, such as going to the pubs in the evening or dancing halls or spending time watching television with the family.

This movement of the indigenous workers into new fields to take up the day time jobscreated a vacuum of labour especially in the textile and woollen mills. The industrialists wanted the mills to run continuously for 24 hours a day to meet the huge international demand for their products and for that they required workers to work morning, afternoon and night shifts.

Because of the shortage of labour to fill these vacancies, the British Government showed flexibility in the immigration rules and made Britain a free port for anyone from Commonwealth countries to come to the UK and take up employment. No visa was required at the port of entry. An identification as to who he or she was, the date and place of birth and the country he or she came from was the only requirement until about the time when the first Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1962 was passed by the British Parliament.

Migration from Indo-Pak Sub-Continent to Britain

As Britain faced a shortage of mill workers around the late 1950s and early 1960s, semi-literate economic migrants from India and Pakistan started coming to Britain to fill the vacancies in cotton mills and factories in various parts of the country.

Some adventurous Bharuchi Vahora Patels seized this opportunity and migrated to Britain during this period. Dawood Pai, a Bharuchi Vahora Patel of Tankaria living in Mumbai migrated to Britain in 1951 and settled in Coventry (West Midlands). He was followed by his relative Ismail Vadhriwala and Isa Tailor of Hinglot in 1956. They settled in Dewsbury (West Yorkshire). A little later, Ali Muhammad Delawala of Sitpon, Umarji Modhu of Hinglot and Muhammad Karkun of Paguthan followed the trend. From the available information we gathered from our elders in their 70s and 80s, it appears that only a handful of Bharuchi Vahora Patels came to Britain before 1960.

Although a small number of Bharuchi Vahora Patels migrated to Britain during this period, it made a great impact back home in India where the news was spreading thick and fast through friends and relatives amongst the Bharuchi Vahora Patel community, of the people who had migrated and settled in Britain. How to go to Britain became the talk of the town amongst the community throughout the Bharuch District.

During our random survey, we interviewed a well-known Ghazal singer, the late Isa Ughradar, originally of Dahegam who settled in Bolton. Recalling his past, he said that in 1956 he met Abdullah Dhanbhai of Karmad at Saraswati Cinema House in Bharuch when Abdullah told him that he was planning to go to Britain. Soon after, Isa came to know that Abdul Dhanbhai had already reached London.

Isa belonged to a very prosperous farming family who owned over a hundred acres of fertile agricultural land in and around his village Dahegam. But as the curiosity and eagerness to go to Britain was prevalent among the Bharuchi Vahora Patels of the day, Isa was also inspired to try his luck in a foreign land. The word Britain was ringing in his ears all the time as if it was the land full of roses. Therefore, he could not resist the temptation and thus, leaving aside the easy life he was enjoying in Dahegam, he joined the band wagon and came to Britain.

Isa Ughradar’s and other well-to-do Bharuchi Vahora Patel’s migration to Britain substantiate the point made by Dr Makrand Mehta and Dr Shirin Mehta (retired historians of the Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, India) in their book “The Gujarati Diaspora in Britain” (published in 2009): “It is a misconception that Bharuchi Vahora Patels migrated to Britain to escape poverty at home. Not all of them came from a poor background. Most of them were well off in India and came to Britain in search of better opportunities or fantasized about what life was like in Britain.”

As the trend continued, besides Isa, a number of other Bharuchi Vahora Patels with little education arrived in Britain from various villages of the Bharuch District before the first Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1962 came into force. Until then, with Britain being a free port, all one needed was a passport and plane ticket which would cost them 1,800 Rupees (approximately £135) in those days. On arrival, entry would be stamped in their passport by the immigration officials without any questioning, because no visa or any other entry clearance was required. Haji Usman originally of Ikher who now lives in Bolton arrived at Heathrow on 16 March 1962, which was the last day of free entry. With the introduction of the Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1962, Britain ceased to be a free port.

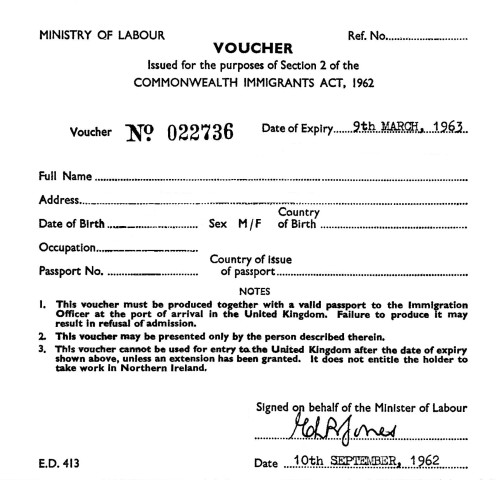

According to that Act, a person from the Commonwealth countries who wanted to come to the UK was required to apply for an entry permit (voucher) through the British High Commission of the country of their abode. Here is a specimen copy of a voucher issued by the Ministry of Labour in London through its High Commission Office in Bombay (Mumbai) on 10 September 1962.

The Act did not fully stop the immigration of people from the Commonwealth countries, it only introduced various categories in the immigration system through which people could come to the UK provided they satisfied the authorities through their applications.

This encouraged well educated, highly qualified and skilled people from India to apply for an entry permit. Educated Bharuchi Vahora Patels were no exception in this respect and therefore, after 1962, a considerable number of them arrived in the UK by obtaining an entry permit (voucher). To mention a few names among them were U M Mastan, A U Patel, Yacoob Mank, Ismail Khunawala and Bashir Khoda of Tankaria. Abdullah Patel Azad (Palia) of Sitpon, Siraj Patel “Paguthanvi” and Abdullah Munshi of Paguthan, Ismail Master of Hinglot, Mohamed Bhuria of Sansrod, Adam Patel Fansiwala of Karmad, Abdul Musa of Janghar, Ismail Vakil of Kantharia and Ismail Kaduji of Nabipur.

Those who came to the UK legally from the Commonwealth countries were given the same rights from day one as the indigenous population.

India was and is a member of the Commonwealth and thus all those Bharuchi Vahora Patels who had settled in Britain became entitled to all those rights. They were given the right of indefinite stay. They could acquire British Nationality if they wished. If they were married, their wives and children under the age of 21 years could join them here. An unmarried man or woman could bring their fiancé / fiancée from overseas and, upon solemnization of the marriage, could get the right of permanent settlement in the UK.

Nearly 99 per cent of the Bharuchi Vahora Patels who had come to the UK by this time and had settled here were already married, but their wives and children were left behind in India. They then decided to call them over to join them. This accelerated the process of migration of families and children to the UK on a large scale. It led to a number of travel agencies appearing unexpectedly in and around Bharuch providing passport services, visas, plane tickets, etc.

Ahmed Bajibhai Sarnarwala, who arrived in 1960, describes the living conditions existing in those days in Britain. This sounds unbelievable but it is very true. He remembers that, when he landed at Heathrow Airport, the airport looked like a deserted Nabipur (a village near Bharuch) railway station.Bajibhai, a newcomer from India landed there with some bedding on his shoulder and three pounds sterling of foreign exchange in his pocket. He did not have a proper knowledge of either spoken or written English, which started creating problems right from the moment he set foot on this foreign land. He had in his pocket the address of a Bharuchi Vahora Patel living in Preston, Lancashire, given to him in India by someone, but he did not know how to proceed there from Heathrow Airport. Before he departed from India, he was advised to hire a taxi from the airport to Euston main line railway station to catch a train to Preston. Since Bajibhai did not have enough knowledge of the English language to communicate, he was feeling very nervous. He did not know how to hire a taxi and had no idea about either Euston railway station or the departure time of a train to Preston or how far Euston was from Heathrow. To add to his misery, the weather on that day was very cold and awful, which he had never experienced in India.

In spite of these problems and difficulties, Bajibhai, just like a number of other adventurous Bharuchi Vahora Patels, braved the situation and somehow managed to find his way to Euston and from there to Preston.

Standard of living, work and life style of Bharuchi Vahora Patels settled in the UK in the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s:

Musa Hasan, originally of Umaraj, who migrated to Britain in 1960 and at present lives in Bolton, relates his experience of those early years, which give us a very good picture of the conditions that existed then and the enormous difficulties and hardships the first settlers from the Bharuchi Vahora Patel community went through.

Musa Hasan tells us that during the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, the life in Britain was not that easy as was visualised from five thousand miles away in India. The new comers were faced with numerous difficulties relating to:

(a) Accommodation;

(b) Food, as they were not accustomed to eating English food;

(c) Communication difficulties, due to the lack of knowledge of the English language;

(d) Arduous working conditions;

(e) Severe weather, i.e. several inches of snow, ice, hail stones, freezing cold spells and biting northerly winds.

Initially, people had come without their families. Only a handful of Bharuchi Vahora Patels owned their houses by getting a mortgage from either the Local Authorities or the Building Societies. They were required to pay cumulative interest on the loan, which was very high. Those Bharuchi Vahora Patels who owned their house were repaying their mortgage by charging rent to those who were living in that house. Normally, the weekly rent charged by thelandlord was £1. The houses owned by Bharuchi Vahora Patels were over-crowded because, apart from a few exceptions, the majority of them wanted to live together for obvious reasons.

During our survey, Usman Haji who lives in Bolton, recalling his memories said that at one time 25 people lived in one old terraced house in Bolton that was owned by a Vahora nick named Little Patel of Ikher. Imagine 25 people living in a 2 bedroom house! It shows the difficulties that the first batch of Vahora migrants had to put up with in those early days of settlement.It would be unthinkable for our present young generation to live in the conditions in which their fathers, grandfathers or great grandfathers lived.

Overcrowding was not the only problem. Nearly 95 per cent of the houses where Bharuchi Vahora Patels were living had no bathroom and the toilets were outside in the back yard. During the winter, due to several inches of snow and freezing temperatures, the water in the pipe connecting to the toilet cistern would freeze and people had to leave a kerosene lamp on overnight inside the water closet to prevent this from happening.

Having no bathrooms in the houses, they had to go to the town centre to a Public Bathand this would mostly be on Saturday afternoon, as people were working from Monday to Friday. Everybody was required to pay a Half Crown (two and a half shillings) and had to wait their turn in a queue. None of the Bharuchi Vahora Patels had any transport, i.e. a car or a van of their own, so they had to walk nearly three quarters of a mile to go to the Public Bath in all sorts of weather conditions.

Some resourceful Bharuchi Vahora Patels were looking for a solution to this weekly problem. Although nearly 90 per cent of them were semi-literate or did not have an education further than the boundaries of their village school, they were neither daft nor unintelligent. Very soon, they started converting the coal bunker in the backyard of their house into a bathroom and, with a gas geyser installed, the problem was soon solved. This make believe bunker bathroom not only served the purpose but also saved them the payment of a Half Crown, which was a considerable amount in those days compared to their very low weekly earnings.

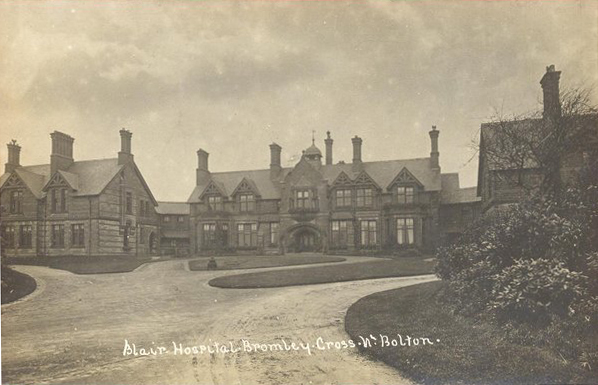

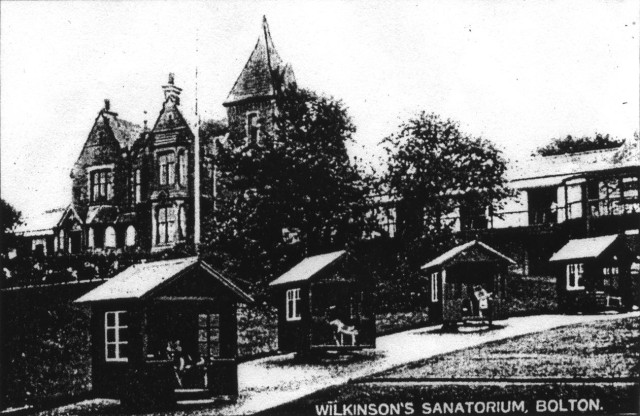

Because of the damp overcrowded houses and malnutrition coupled with working in cotton mills, many people became victims of TB (tuberculosis). According to the information provided by Bashir Chhadat of Bolton, the Blair’s Hospital in Bromley Cross and Wilkinson Sanatorium on Belmont Road were full of TB patients who were Asians.

Very few houses had black and white television sets (colour televisions were not yet marketed). In fact people did not have much spare time to sit in front of the box and watch any programmes. There were no landline telephones where Asians were living, so Bharuchi Vahora Patels got news from their homeland through either letters received from their relatives or in some cases old newspapers sent by someone from India. Urgent messages of serious illness or death in the family back home were received by telegram. Such telegrams were in English, so they had to be translated by an English knowing person.

There were no masjids in existence, so those who wanted to offer prayersdid so in the houses that they lived in. In the early days, people were hardly aware of Ramadan or Eid. Later on, as the migrant Muslim population of Bharuchi Vahora Patels, Surti Sunni Vahoras and Pakistanis increased, Town Halls were booked for Eid prayers. During the summer time, if the weather was good, Eid prayers were held in public parks as well.

Elderly Bharuchi Vahora Patels who came to Britain in the 1960s tell us that, in those days, there was a strong sense of brotherhood among the Bharuchi Vahora Patels who always supported each other. They provided accommodation and food free of charge to the newcomers (whether he was a relative or from the same village or not) until he found a job and started earning some money. They even lent him money to send home to pay off debts or if his family were in dire need. They even took him to various factories to find a job. Thus, the first generation of Bharuchi Vahora Patels in Britain survived and settled through wonderful comradeship and mutual help. They toiled in factories during the weekdays, but put on a suit and necktieat the weekends and partied at friends’ houses.

Food:

Nearly 99 per cent of Bharuchi Vahora Patels did not know how to cook. This was because they were never required to prepare a meal back at home in India. There, everything connected with cooking and other household chores was done by women. Here in Britain they were in a different situation. Bharuchi Vahora Patels were on their own, as their families were still in India and they were required to cook food themselves. It was a problem. Some did not even know how to use a gas cooker or its oven because the village they had come from did not have gas cookers. For them it was an unknown entity. To add to their misery, the items for the type of food they were habituated to eat like Bhinda, Daal, Khichadi and Kadhee, Mung, Tuver, etc were not available and neither was the halal meat. So these earlier migrants had to make do with simple bread, butter, beans, eggs and potatoes.

Chickens were available but, because they were not halal, they were not acceptable to Bharuchi Vahora Patels. Soon, they found a way to overcome this difficulty. In those days, milk was delivered to the door step by a milkman. They used the services of the milkman to find out where the poultry farm was, where they could go to buy some live chickens and do the halal slaughter. This was arranged and soon they were all enjoying the soft, juicy hens and baby chickens of Britain.

Buying chicken was no problem. But buying a margho (cock) posed a problem, as they did not know the English word for it. Trying to explain this to the poultry farm owner, one Bharuchi Vahora Patel came up with the magic term “chicken husband”, which made the owner burst into laughter but the message got through and they ended up buying what they wanted – a margho!

Shopping:

Not knowing the English names for the items they wanted to buy did not pose much of a problem for these early settlers because, when out shopping, they would normally point at the items displayed in the shop or the market. The only difficulty would arise if the item was not on display when sign language would be used to get the message through to the shopkeeper.

Work and working conditions:

During the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s the weather, especially in winter, was atrocious. People had to go to work in freezing temperatures. Most of them worked night shifts in mills. It was hard work – doffing, spinning, weaving, winding, cleaning, packing etc. No Vahora owned a car, so people used buses to go to work.

The wages in the mills and factories were very low. Normally it was in the region of £7 to £10 gross per week. Therefore, after the compulsory deduction of National Insurance Contributions and Income Tax, the net earning was only around £6 to £8 per week.

Musa Hasan of Umaraj recalls those difficult days and tells us that he came to Britain in January 1960, took up work in a carpet factory in Kendal in the Lake District and worked seven days a week. While working there, he lived with an English family as a paying guest.

The well-known Courtaulds Limited of Preston in Lancashire, which produced man-made fibres, was the only mill paying around £12 to £14 a week to its workers, but this was because there they had to work with acid, which used to cause blisters in their hands. To improve the poor working conditions and wages, in 1964, the first workers strike in the history of Courtaulds Mill was led by Abdullah Patel Azad, a graduate from the University of Bombay, residing in Preston and originally from Sitpon.

When Courtaulds could not compete with the man-made fibre producing foreign countries, it closed its production line in Preston in 1979. Around 2,600 workers lost their jobs, of which a large number of workers were Asians, including very many Bharuchi Vahora Patels.

Arrivals of Bharuchi Vahora Patel families in Britain:

By the late 1970s, quite a few Bharuchi Vahora Patels had bought cheaper houses in mostly run-down areas. In such areas, the houses would cost between £200 to £500 depending upon their condition and the amenities they had, like inside toilets or bathrooms.

It was around this period when families started arriving from India. The first generation of Vahora women also faced immense difficulties in those days. As mentioned before, there was no bathroom or toilet inside the house, no washing machine, no instant hot water. Disposable nappies did not exist then, which meant that the cotton towel nappies they used had to be washed by hand, using cold water. In addition to the tedious household chores, they had to work in a mill or factory to add to the family income.

Establishment of masjids

As soon as Bharuchi Vahora Patels became self-sufficient, their first concern was to establish masjids to pray and madrasas to provide Islamic education for their children. They called Islamic teachers from India. Gradually the first generation of enthusiastic and religious-minded Bharuchi Vahora Patels through their own hard earned money founded an excellent network of Islamic institutions in Britain. It is Bharuchi Vahora Patels who made a major contribution, financial and otherwise, in the establishment of the very first Darul Uloom of Lancashire in Ramsbottom, Bury.

Education:

Bharuchi Vahora Patels also started thinking in terms of the secular education of their children in an Islamic environment. The first movement for Muslim faith schools was started by Abdullah Patel Azad of Sitpon who lived in Bradford, Yorkshire. Inspired by this, Bharuchi Vahora Patels took the lead and started single sex high schools for girls only in Blackburn and Bolton with little knowledge of school management and extremely meagre resources. Both of these schools have now become Government grant aided schools.

This semi-literate but sincere and practical first generation of Bharuchi Vahora Patels in Britain worked extremely hard and showed great insight in paving the path for our future generations in this country. They sacrificed their time and hard earned money to found institutions that are needed to preserve our faith and our identity. What they have achieved with little education and very limited resources in a foreign land is simply amazing and awe-inspiring. It must be acknowledged by the younger generation who should strive to build on it and take it further.

In the 1970s, when the families came, they were accompanied by children of a very young age. These children went to schools where the medium of instruction was English. Because of this language problem, they could not make much progress in their studies. The young Bharuchi Vahora Patels of the second generation normally completed their high school education and took up jobs.

During the premiership of Margret Thatcher, the cotton mills closed down and many Bharuchi Vahora Patels lost their jobs. This compelled them to look for other avenues. Some of them started their own businesses. Quite a few became owners of corner shops and more enterprising Bharuchi Vahora Patels started curtain, garment and shoe manufacturing factories. Sufi Manubari was the first Bharuchi Vahora Patel to open an Asian Take Away, selling hot samosas and pakoras, on Halliwell Road in Bolton.

Bharuchi Vahora Patels had come to Britain for a better standard of living. This was achieved by the second generation through hard work. The women also contributed by working at home, mostly as sewing machinists. Sewing garments at home became like a cottage industry and increased their household income, which made it possible for them to buy their own houses and furnish them with carpets, fridge-freezer, sofa sets, television, vacuum cleaner, washing machine, etc.

Instead of becoming selfish with the increased prosperity, they extended a helping hand to their poor relatives in India. Not only that, they donated money to charities to help widows and orphans in the community and those others who were in desperate need. They also supported a number of educational and welfare projects like hospitals, masjids, madrasas, musafirkhanas (guest houses), schools, water works, etc. The incessant flow of their generous donations has changed the condition of the villages back home in more than one respect.

The British Bharuchi Vahora Patels prospered in many ways. The third generation born and brought up in Britain inherited the wealth and prosperity which was the result of the hard work of their parents and grandparents.

Bharuchi Vahora Patels have been in Britain for over half a century now. It is important to know how the first migrants came to this country, what hardships they faced and how they achieved prosperity through their hard work, frugal living and wise money management. It is essential for the younger generation to know about our past and to appreciate the sacrifices and the endeavours made by the previous generations to reach where we are today.

The aim of this book is to make our younger generation aware of our roots and enable them to:

- see and understand where we stand today in terms of educational, economic, political, social, religious and cultural progress;

- become familiar with our social values;

- identify our social problems and become active for their solution;

- identify themselves with the Bharuchi Vahora Patel community and become part of it;

- internalise our values and traditions;

- adjust themselves with the social structure and make their own contribution to the well-being and development of our people;

- and finally, to ensure that our identity as Bharuchi Vahora Patels is well preserved and not lost in the years to come as has happened in the case of other communities settled in various countries of Europe.

Bharuchi Vahora Patels are mainly populated in the textile towns such as Blackburn, Dewsbury, Bolton, Lancaster, Manchester and Preston in the north of England. Considerable number of Bharuchi Vahora Patels resides in Birmingham, Leicester and London, with a small number in Chorley, Coventry and Nuneaton. With the help of our friends and social workers, we have collected some useful information in respect of the past and present status of our people in these towns and cities.

Because of the limited resources and the lack of a network, the information presented here may be incomplete or may appear to be not accurate.

In addition to the facts related to our past and present, we have also attempted a study of the problems facing our community in Britain. Through a questionnaire, we tried to find out how the youngsters of our community perceive our problems and how they think these can be resolved. We had sent a questionnaire to a large number of young people, but very few responded. Because of the small sample, we do not consider that this is a representative survey of our problems. Nevertheless, we feel that this will give Bharuchi Vahora Patels some indication as to the nature of our problems and the ways of solving them.

Our friends and social workers have painstakingly collected the information regarding the Bharuchi Vahora Patels settled in various places. This information is presented in the chapters that now follow.