Bharuchi Vahora Patel – Pre-Independence Era

Social structure:

In 1877, the Bombay Provincial Government (during the British Raj) published the “Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Surat and Broach”. And again in 1899, the Provincial Government carried out another survey and published the “Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency Gujarat Population: Musalmaan and Parsi”. These two documents contain detailed and very useful information about the Bharuchi Vahora Patel Society during the late nineteenth century.

The gist of the relevant information, as recorded in these Gazetteers, is that many villages of Bharuch district have a large Vahora population. In appearance, bodily structure and life-style they resemble Hindu farmers. They are competent and hard-working. They are pleasant and sociable by nature. Their hospitality is well known. Their women are active, industrious, eloquent and good looking. Apart from doing embroidery and weaving, Bharuchi Vahora Patel Women help their men-folk in farming as well. And they have a dominant role in household affairs.

Bharuchi Vahora Patels have their own exclusive social structure. They do not indulge in inter-marriages with Surti Sunni Vahoras but do maintain all other relations with them. In the villages of Bharuch district, heads of the village councils are Bharuchi Vahora Patels. Hindu farmers respect them very much. If ever their bullock carts confront each other in a narrow track, the Hindu farmer generally gives way and lets the Bharuchi Vahora Patel pass first.

It is further mentioned in the Gazetteer that Vahora men are hot tempered, fanatic and independent-minded. Because of their violent nature, the non-Muslims of Broach (Bharuch) call them Soldier Lok (Army People). Citing an example, the Gazetteer notes that on 15 May 1875, two hundred Vahoras from the surrounding villages marched on to Broach to teach a lesson to a Parsi who had insulted their Prophet (peace be upon him) and hurt their religious feelings. This Parsi met his fate at the hands of the angry mob. They are courageous, hospitable and religious minded people. Men shave their heads, keep beards and wear salwar (loose trousers) and shirt.

Some men wear a head dress (a long piece of cloth twisted and wound round the head in circles), put on a turban or red or black cap.

The Gazetteer gives us a good insight of a well-to-do Vahora with an annual income of 1,000 rupees (a very big amount in the nineteenth century). It states that a Vahora with such a good income keeps two turbans worth 30 rupees each, eight cotton jackets worth 12 aanaas (¾ of a rupee) each, eight waist coats worth 1½ rupees each, eight trousers worth 1 rupee each and four khes (shoulder cloths) worth 2½ rupees each. In addition to such a huge wardrobe, a Bharuchi Vahora Patel with an annual income of such magnitude would also have in his collection a gold embroidered turban worth 100 rupees and a velvet jacket worth 70 rupees and shoes worth 3 rupees to wear on special occasions. Some Bharuchi Vahora Patels put on a pachhedi (an unstitched upper cloth) and kachhio (under wear). If they go to the court or Government offices, they put on a shirt with buttons made of gold and a shervaani (long coat).

Wives of Bharuchi Vahora Patel farmers wear a sari (a loose cloth of approximately three to five meters long wrapped around the whole body); cholee (blouse) and chaniyo or ghaghara (long skirt). They wear sapaat (foot slippers). They wear gold ornaments such as a damani (head chain), tilak (dot) on their forehead, nathly (nose ring), rings on their fingers, ear rings (made of silver and worn by piercing their ears), gold coated necklace type ornaments popularly known as kanthee, katesari (waistband), momno (locket made of glass beads), kambbi (silver leg bangles) and sankla (anklets). Their ornaments are beautifully designed, thick and heavy in weight.

The Bharuchi Vahora Patels’ pronunciation of the Gujarati language and accent are different from those of the Daudi Vahora. They distort and pronounce Muslim names such as Ibrahim as Abhlo, Ismail as Asmaal, Vali as Valyo, Yusuf as Ispo, Aamena as Amli, Ayesha as Aahli and Fatema as Fatli.

Khichadi (boiled rice mixed with lentils) and kadhee (curry soup made from yogurt) is their staple diet. Apart from this, they consume a variety of other food such as fish curry, fried fish, meat curry, vegetable curry, plain rice or pilau rice and coarse bread made from jawaar flour, millet or wheat flour. According to the Gazetteer, alcoholic drinks were non-existent among Bharuchi Vahora Patels, although a few were habituated to smoke ganjo (opium). However, if they lost their senses and misbehaved after consuming opium, the community would look at them with disrespect and hate them. Their social structure is rigid and they hardly ever marry outside their own caste.

Bharuchi Vahora Patels still follow some Hindu customs. Like Hindus, their women mourn the dead by crying and beating the chest. And at the beginning of a wedding ceremony, just three days before the wedding, they distribute boiled laang (lentils) and vaal (brown chickpeas) in the name of Vaanudev, a Hindu wedding custom that is also known as the vono ceremony. At night, village women gather at the houses of both the bride and the bridegroom and sing wedding songs and apply turmeric paste on their face, hands and feet. This ceremony is known as peethi, which nowadays is also known as mahendi (henna) among the Bharuchi Vahora Patels.

The Gazetteer, in its survey, notes that like Hindus, Bharuchi Vahora Patels also arrange community dinners on various occasions such as weddings, deaths or when a woman conceives. Because printing presses did not exist in the villages, Bharuchi Vahora Patels had their own interesting method of extending invitations. They would prepare a list of invitees and would give that list to the village barber who would go round the community and verbally invite those who were on the list. Wedding meals would be prepared mostly in the open air and it is customary for men to eat first and the women afterwards. The village barber was considered to be a very important person for such occasions and, for his services, he would be honoured in kind as well as in cash by the party concerned. This system of extending invitations is still in use in the villages.

On the wedding day, the groom along with relatives and invited guests goes to the bride’s residence in the form of a procession led by a music band including drums and approximately four to five feet long trumpets known as dhaturu. In the procession, women would walk behind the men folk and sing wedding songs. When the procession reaches the bride’s residence, ladies from both sides come face to face with each other and start teasing one another by singing humorous and sarcastic wedding songs. Sometimes they overdo it, which results in swearing and bitter arguments. But it’s all intended to be fun – an innocent customary way of enjoying wedding celebrations, especially by women.

Here are some typical wedding songs:

Taara monmaa oyraa mug

Balaadaa bolto kem nathee

These couplets are specifically sung by the women from the bride’s side to tease the groom when he arrives in a procession at the bride’s residence. Referring to the groom as a tomcat, the women sing:

Is your mouth full of mung beans?

You tomcat, why don’t you utter a single word?

(Or are you scared of your soon-to-be wife? Ha..Ha..Ha..).

In retaliation, the women who are in the procession from the groom’s side would retort by singing:

Taaraa ghar maa nathee karso

Tyaare shinne teyro navso

Maaraa navlaa vevaay

Tane doodh ne saker paun

When you do not have even a small water jug in your house to serve water;

Then why did you invite the groom to your place?

Well, we do understand your situation;

Don’t worry, since we have established a new relationship, in place of water we will offer you milkshake to quench your thirst.

These wedding songs are sung by both parties to tease one another as a form of clean fun and not in an offensive or derogatory way. They give ample opportunity, especially to womenfolk, to express their joy and fun in the company of other women.

At the peethi ceremony, they sing:

Musabhai ni laakadiyo

Ne Mariyam vouv naa bayda

Laakadiyo tau bhaagi geyo

Ne bevad vayraa bayda

Jovo re loko vonaa naa tamaashaa

In a joyous teasing mood, women sing:

Musabhai (the groom) has got hold of a stick and, to test the strength of it, he lashes it onto the back of Mariyam (his bride).

What a pity! Although unintentional, Mariyam has got seriously injured and the stick has broken into pieces.

O people! Come and see the farce of peethi.

Agriculture:

The Gazetteer gives a lot of information in respect of agriculture and its allied trades. It states that the Bharuchi Vahora Patel farmers grow chanaa (chickpeas), cotton, groundnuts, jawaar, lentils, rice and sesame seeds. In addition to farming, they are actively involved in rural trading and marketing. The Government of the East India Company has created Cotton Experimental Farms in the Bharuch District to improve the quality of cotton. The chief of the project was James Landen. In 1855 he set up a ginning and spinning mill in Bharuch, which was the first cotton mill of its kind in India. The machinery for this mill was manufactured in Blackburn, UK, imported through the Manchester Cotton Exchange and shipped to India from its nearest port Liverpool.

The 1899 Gazetteer points out: “the Vahora cotton growers sell their cotton to Landen’s mill through its agents, where the cotton goes through the ginning and spinning process.”Apart from the senior management, the rest of the mill workers are mostly ordinary, poor, uneducated Indians living in Bharuch and its surrounding area.

In view of the expansion of the cotton sector in Bharuch, a Parsi named Jamshedji Vakharia took the opportunity to act as an agent to buy cotton from the farmers and sell it to Landen’s mill. As it became a flourishing business, he established his own small ginning factories in Bharuch and Palej. The Bharuch complex became known as Jamshedji Vakharia Jeen. Palej became the centre of cotton trade, as it was in the midst of a number of villages growing cotton. The ginning factory in Palej was owned by Jamshedji’s son, Jal Sheth Jamshedji Vakharia, but it was managed by Bharuchi Vahora Patels.

Bharuchi Vahora Patels are basically farmers but, because of their courageous nature, they are in the police force and, due to their skills, some of them have their own businesses.

Education:

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Bharuchi Vahora Patels started sending their children to schools. The first graduate amongst the Bharuchi Vahora Patels was Khan Bahadur Vali Bux Patel, from Sitpon, who graduated in the year 1900. After obtaining his degree, he joined the Revenue Department.

In 1916, Ali Patel of Kantharia acquired his LLB degree and started a legal practice in Bharuch. Because of his legal practice, he became known as Ali Vakil (Lawyer) among the community. In 1923, he was elected as a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly. It was he who was the founder of Anjuman-e-Islam and the first Bharuchi Vahora Patel to establish a school and a library in Bharuch.

Musaji Isakji Patel, another Vahora dignitary, was a High Court Judge in Junagadh, Saurashtra. Later on he was appointed as the Deputy Charity Commissioner in Ahmedabad.

Muhammad Vali Janab, from Tankaria, was Secretary to the Chief Minister of Junagadh, Saurashtra.

Ali Dadabhai Patel, also from Tankaria, qualified in 1912 as the first physician amongst the Bharuchi Vahora community. He was a civil surgeon in Bharuch and a member of the Bombay Province Medical Council. After retirement, he opened his own nursing home in Bharuch.

Politics:

Taking into consideration the agitation and rebellion in 1857, by the Hindus and Muslims of India acting jointly against the British Raj, and the subsequent situations arising in India, Lord Ripon suggested to Queen Victoria’s Government in Britain to show some flexibility to calm the uprising by introducing some sort of Home Rule. The Queen’s Government, taking into consideration the suggestion, passed the Local Government Home Rule Act in 1884, thereby allowing the Indians to participate in politics. Taking advantage of this reform, many Bharuchi Vahora Patels took part in elections and entered the District Local Boards and Municipalities as elected members.

The active participation of Bharuchi Vahora Patels in the political arena accelerated with the lapse of time during the British Raj and, as has been mentioned earlier, KhanBahadur Ali Patel, from Kantharia, was elected to the Bombay Legislative Assembly in 1923.

In 1932 Vali Bux Patel of Sitpon became an MLA (Member of Legislative Assembly).

Ahmed Adam Patel of Sarod served as an MLA from 1946 to 1951.

Muhammad Ibrahim Makkan of Kolavna and Musa Hasan Saleh of Vora-Samni were awarded the title of Khan Sahib (Leader Sir) by the British Government.

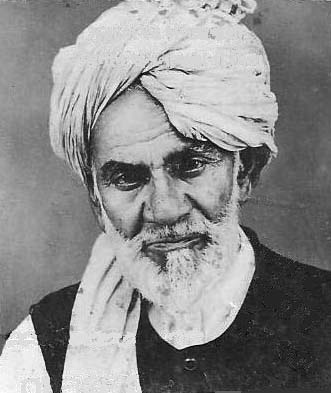

According to the information provided by Dawood Azad, from the Bharuch District, presently living in London, Musa Hasan Khan Sahib was born in 1849. He had completed only the first year of primary education, but Allah had bestowed him with intelligence, wisdom and common sense.

This earned him a very respectful status in the community and beyond. In recognition of his services, the then British Governor, Sir Lawrence Roger Lumley, personally came to Vora-Samni and honoured him with a gold medal and the title of Khan Sahib. During his long life of 108 years, he was a witness to the two major events in the history of India, namely the uprising against the British Rule in 1857 and the independence of India in 1947.

Another personality from among the Bharuchi Vahora Patels,Dr Ali Patel from Tankaria, was elected to the Bombay Legislative Assembly uncontested. He was also the President of the Bharuch District Muslim League, which drew its committee members from among the cross section of the Muslim community. The League’s meetings were held on the first floor of Bismillah Hotel in Katopor Bazaar, Bharuch.

Many other Bharuchi Vahora Patels were also elected as members of the District Local Board. These include Ismail Akuji Patel of Sarod, Muhammad Master Ghodiwala of Tankaria, Vali Saleh of Zanghar, Suleman Amiji of Nabipur and Vali Ahmed Suleman Member of Paguthan who was also the elected member of Bharuch Borough Municipality and sub-editor of Bharuch Samachar (News) – the press and the newspaper was owned by a Parsi family of Bharuch.

Bharuchi Vahora Patels responded positively to the call for freeing the country from the British Raj and joined countless Indians who took an active part in the freedom movement of India. Within the Bharuchi Vahora Patel community, there were a number of supporters of Gandhiji. Freedom fighters among the Bharuchi Vahora Patels were Mahatma Adam Kabir, Musa Isa Captain, Dr Ali Ghodiwala, Adam Ismail Mustufabadi and Ibrahim Nayak who were all from Tankaria. Rafik Munshi of Kavi and Musa Hasan of Vora Samni also took part in the freedom movement. Haji Ibrahimbhai Ali Manbhad of Ikhar village took part in the historic Dandikuch (Dandi march) with Gandhiji which was to protest against the 1982 British Salt Act. As the British Government who were ruling over India did not approve of the freedom movement, they started detaining and putting a large number of people in jails throughout India. Mahatma Kabir and Musa Isa Captain of Tankaria were sent to Nagpur Jail. After India became independent on 15 August 1947, they were entitled to Freedom Fighters’ Pension. However, these patriotic Bharuchi Vahora Patels did not even apply to receive this pension.

The history of the independence of India (1857 to 1947) bears ample evidence that Muslims throughout India in general and the Bharuchi Vahora Patels in particular were part and parcel of the freedom movement along with all the other communities including Bengalis, Hindus, Sikhs etc. These brave freedom fighters are remembered every year in India on Independence Day.

Literature:

The Bharuchi Vahora Patel’s contribution to Gujarati literature is very significant. 250 years ago, Abhram Bhagat, a Bharuchi Vahora Patel of Pariej composed devotional songs that are sung even today. He was a disciple of Pir Qayamuddin of Ekalbara and was the one chosen by the Pir for enlightenment.

Abhram Bhagat, through his bhajans (devotional songs), has expressed the oneness of Allah and the love for the Prophet (peace be upon him). This is what he has to say about idol worshipping:

PutloN ne pooje re Saheb nahiN male re ji,

Teno tau nyaaro chhe vaLee desh.You will not find God by worshiping idols, my friend,

His existence is indeed unique.Pani maa naakho re pathraa tau Doobshe re ji,

Tene pooje thi tu kem re taresh.

If you throw stones in water, they will sink, my friend,

How will you be able to swim the ocean of life by worshipping them.

Abhram Bhagat was an illiterate farmer and, in his bhajans, he beautifully expresses his spiritual experiences in terminology which he derives from his knowledge as a farmer.

Late Ibrahim Dadabhai “Bekar”, a Bharuchi Vahora Patel of Khanpur, was a renowned humourist and satirical writer, occupying a prominent place in Gujarati literature. In 1932, he founded Muslim Sahitya Mandal (Literary Circle). Through mushairas (poetry recitals) he played a leading role in popularising the ghazal and hazal form of poetry in the Gujarati language.

He was not only a poet, but a good writer as well. He edited and published a monthly magazine called “Patel Mitra”, which was later re-named “Insaan”. The magazine served as a forum for the Bharuchi Vahora Patel community. In 1954, he compiled and published the “Patel Directory” which contains some useful information about prominent Bharuchi Vahora Patels of his time settled in various parts of the world.

There were other contemporary poets and writers of “Bekar” in various villages of the Bharuch district. Well known among them were Mast Habib Sarodi and Umarji E Sarodi; Adam Ismail Mustufabadi, “Majnoo”, Isa Delawala, “Bedar” Tankarvi, Ismail Mura-Munshi, “Patil” Tankarvi, Ibrahim Adam “Kabir” Tankarvi, Ahmed Agar “Divya” Tankarvi, Vali Patel and Yusuf Ashraf of Vahaalu, “Gumnaam” of Jambusar and Vali Ahmed Member of Paguthan. Besides these, Adam and Ghafeel were also known during this period.

In addition to the above, another notable writer and reformist of that period was the late Yusuf Munshi Kaviwala. He was the editor of a monthly magazine called Paigaam and through this publication he tirelessly endeavoured to bring about the reforms much needed within the Bharuchi Vahora Patel community.

In one of his articles “Are we mo’meen (believers) or munafiq (hypocrites)”, he writes about Bharuchi Vahora Patels and their shameless use of four letter words even in their normal day to day conversations:

“Bharuchi Vahora Patels reveal their identity as soon as they open their mouth – you don’t need to ask them. This is due to the fact that we, the Bharuchi Vahora Patels, not only start our normal conversation with swear words, but continue the talk or carry on gossiping in the same manner thoughtlessly using four letter words in each and every sentence we speak. Consequently, there are more swearing words than actual content in our normal conversation.

Two Bharuchi Vahora Patels talking to each other, raising their voice and shamelessly using swear words, gives an onlooker the impression that here are two people about to come to blows. Because of such bad habits, we the Bharuchi Vahora Patels are losing our credibility and reputation and are perceived by other communities as indecent people, not worth mingling with. This frequently puts us into troubles of all sorts and we stand to lose a lot because of such ill manners. Regrettably we, as a Bharuchi Vahora Patel community, have never tried to eliminate our munafiqin (hypocritical) habits / attitude.

Foul language has become part of our culture to such an extent that people don’t hesitate to use indecent dirty words even in the presence of their mothers, sisters and daughters. This carries on in their homes, at public events and functions, such as weddings and meetings, and no one feels ashamed or embarrassed about it. Abusive language, coupled with four letter words, has become a trademark of the Bharuchi Vahora Patels.”

It should be noted, however, that in the last few years the situation appears to have improved and people are becoming more aware and sensible. Slowly, but surely, they are getting rid of their bad habits, with the result that, now, Bharuchi Vahora Patels do hesitate to use bad language in front of others in public places. In spite of such improvement, it is still observed in villages that if two individuals are having an argument or a fight, unimaginable swear words are used by both parties, as if it’s raining filth from their dirty mouths.

Finally, it is hoped and also desired that honourable teachers and religious scholars continue to do all they can, through their guidance and lectures, to rectify the bad habits prevalent in the community.